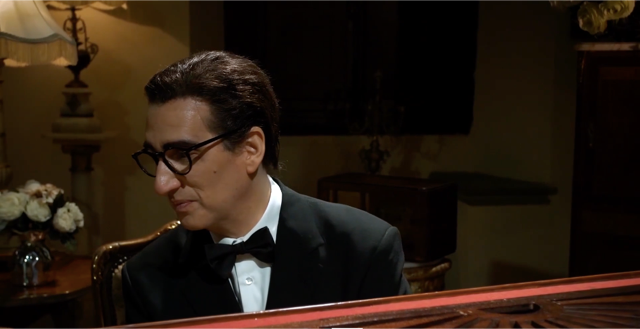

HERSHEY FELDER AS IRVING BERLIN

THE ROAD TO ‘HERSHEY FELDER AS IRVING BERLIN’

My relationship with Irving Berlin, America’s greatest songwriter, began twenty-four years ago, when I was just beginning to learn about the beauties of the great American Songbook and its contributors. I was in my twenties, I was able to read fine print without the aid of what I then believed were “old person’s reading glasses” (I’m still at “1,” but for how long, who knows?), and I had just begun devouring traditional American music. Up until that point I had been steeped in European lore, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, with dashes of Russkye Vodka thrown in…Rachmaninoff in particular. As a first generation North American with most of my immediate relatives speaking with heavy European accents, I felt at home in a European milieu, as well as feeling a certain disconnect with American pop culture given that I didn’t really know much about current musical fashion at the time except for ‘Grease,' and 'Saturday Night Fever,' and that was only due to the need to keep up with everyone else at grade school. What I did identify with however were the origins of these great composers, be it George Gershwin, Irving Berlin, or Leonard Bernstein, all of whom I ended up playing on stage, in that I too was a first-generation child of Eastern European immigrants. And like my own parents, these great composers’ parents brought the 'Old World' to America with them and expected that their sons would live that way irrespective of the New World’s demands. And yet there is a story with regard to Irving Berlin, that while it may be apocryphal, its essence has been confirmed to me by Mary Ellin Barret, Irving Berlin’s eldest daughter.

In 1896, Irving was eight years old, having arrived to America only three years before with his entire eight person family (plus a lodger, for much needed extra pennies) now packed into the semi squalor of a Lower East Side New York tenement. His older sisters rolled cigars, his brother sewed shirts, and his mother helped anyone in the neighborhood requiring the services of a midwife. Everyone had to work, and everyone had to bring home their pennies to support the family. Eight year old Irving had a job selling newspapers on the streets for a penny a paper. Every day he would return home from the dirty streets of lower Manhattan, and immediately turn his pennies over to his mother. To little Izzy - Yisroel Beilin, (Irving’s birth name) - an eight year old whose only memory of his birthplace was a Russian pogrom that destroyed his village, giving away his hard earned pennies with no real explanation as to why, seemed wholly unfair. One day, Izzy - Irving, already known for his overwhelming emotions and quick tongue, snapped at his mother…

“This is not fair. I hate America.”

His mother, Leah, matronly but loving, with clearly an even sharper tongue than her son, replied:

“God Bless America, and don’t you ever forget it.”

In this little story, the seeds of everything Irving Berlin are already sewn. He is clearly a sensitive boy with emotions bubbling at the surface and he has a need to express them in the most direct way possible, as he does so clearly in his songs. He is taught the value of family members as he delivers his pennies each day into his mother’s apron to take care of them, but also learns the value of “why” one must work, and that is to take care of others. His mother reminds him of the notion that whether he likes his work or not, in America, he is free to do it, and above all, given that we know what happened with these few words that his mother is said to have uttered - he had a mind like a steel trap, and was able to store information and emotion in that proverbial “trunk” and call on it for musical, lyrical, and emotional purposes, when the time was right. For most of Irving Berlin’s 101 years, these were the standards that guided his every action, until the New World America that he came to love and call home changed, and he had difficulty changing along with it.

Like many people, I knew the songs “God Bless America,” “White Christmas,” “There’s no Business Like Show Business” and a few others because it seemed that they were always part of the American musical fabric. But my fleeting knowledge of these songs was more due to the popular cultural institutions they were associated with than anything; be it a song being sung in a baseball stadium, or in the shopping mall every November and December, or as an anthem for anyone who likes being on stage, or just likes being the center of attention. I knew in some peripheral way that these songs had been composed by Irving Berlin, the little of whom I knew because of my study of George Gershwin, composer of “A Rhapsody in Blue,” given that that was the first American concert piece I played in public with orchestra when I was 19. Berlin had called Gershwin “the only songwriter I knew who grew up to be a composer.” Later on, when George was extremely ill with an as-of-yet undiagnosed brain tumor, Irving Berlin told the press that “there is nothing wrong with George Gershwin that a hit tune wouldn’t cure.” When I first read that, I thought “What a terrible thing to say.” It was only later on that I understood that Irving was protecting his friend George from the prying eyes of the press, essentially denying the rampant rumors of mental illness (and not a brain tumor which is what George suffered from) among other things by effectively saying “leave him alone.” In fact the second to last photo of George Gershwin is a “selfie” that George, fascinated with gadgets, (you can even see George pressing what appears to be the auto shutter button in this image) took of himself and his friend Irving Berlin in George’s Beverly Hills living room in the spring of 1937. Several months later, at the age of 38, George Gershwin was dead.

While it was Gershwin’s “A Rhapsody in Blue” and the public’s response to it that inspired me to begin the journey of telling composers’ stories and the contexts for their compositions, I came to Irving Berlin at the gentle suggestions, or rather, the overt insistence of people who knew him, or were somewhat associated.

Twenty years ago, in the spring of 2000, two couples who attended a performance of the Gershwin piece in Hollywood at the now disappeared Tiffany Theatre on Sunset Boulevard waited for me after the show. They insisted on taking me out to dinner, that after such a workout, I needed to be properly fed. They were quite a bit older than I but it seemed like fun, so I went. They took me to the now defunct Jerry’s Deli just down the way. The five us were stuffed into a circular red faux leather booth, and as the waiter approached with menus, the menus were immediately waved away with a straightforward order from the oldest of the lot:

“Bring us pastrami sandwiches all around, with plenty of good fat, two orders of chopped liver, three orders of coleslaw, three orders of pickles, french fries for each person, extra caraway bread, - and the extra special mustard.” Then one of them looked at me.

“Do you need a steak after all that hard work? You look like you need a steak!”

“No,” I said, "but I’d be good with soup. Soup will be enough.” The fellow then turns to the waiter.

“And a matzah-ball soup. Make sure the BALLS ARE REAL BIG.” ALL CAPS being theirs not mine, and there was no irony in the statement, it was just point blank.

It was only minutes later when two waiters arrived with two huge trays of food and they began whizzing all the plates onto the table.

“Bring gravy. We also need gravy.”

I literally could not believe what I was seeing as my bucket of Matzah-ball soup was placed before me, the broth still swishing about, some of it splashing onto the table beside the bowl. Within a second it was like a table of locusts. Hands pushing plates this way and that, bashing into each other, cutlery flying, food on plates falling over the sides, everything being shoved hither and yon, and within minutes it appeared as if a gang of hyenas had inhaled everything in sight leaving only half a soggy french fry here, a sliver of fat from a piece of pastrami there, even the bowl of chopped liver had been wiped clean with the extra caraway bread that was now nowhere to be seen. And then my host lifts an arm and calls over the waiter.

“Cheesecake. We need cheesecake. And more water."

Even the waiter, who had no doubt seen extreme gluttony in his day, appeared to be flummoxed by the situation.”

“A piece of cheesecake with five forks?”

“What piece?” My host says. “A cheesecake. A Cake. The whole thing. And yes. Five forks.”

A mountain-high heart attack on a large, round serving dish arrives. “I don’t suppose you want whipped cream?” The waiter says almost catatonically.

“Of course we do!” The aerosol of whipped cream is left on the table. The waiter turned away, leaving the band of insatiable aliens to fend for themselves. It was clear, he couldn’t believe anything he was seeing.

And so, five people, each with fork in hand, devoured an entire cheesecake leaving nary a crumb. My hosts that evening - these wonderful people full of life and living, with an endless stream of stories that went along in rapid fire succession with each bite were the legendary author Sidney Sheldon and his wife Alexandra, along with their friends, the legendary Steve Allan and his wife Jayne Meadows. They were all that side of eighty in those days. Clearly the mountains of fat in their dinners had kept them well-oiled and running brilliantly. And then there was me and my pitiful bowl of chicken soup with two big balls.

In what could only be construed as a weird little miracle, this bunch adopted me, 55 years younger than their average age, and I found myself invited to stay over at Sidney and Alexandra’s guest house in Beverly Hills when I was in town, or in the house in Palm Desert, while also finding myself at Sidney’s dinner table quite a few times, one night with Red Buttons to one side of me and Sid Caesar to the other. It’s an interesting thing with truly great and gifted people. Not only do they allow you to shine and be an equal, they encourage it. They wanted to hear my jokes. They wanted to hear my stories. They wanted to hear my music. I guess I did somewhat ok, because I kept on getting invited back. While the really funny stuff coming out of these folks was endlessly entertaining and so educational in terms of great art, the real education, was their unbridled generosity of spirit.

One day Sidney asked me to come up to the studio where he worked in a separate building on his hilltop Beverly Hills property just off of Sunset. The building also housed his home movie theatre, which itself housed a pair of ruby slippers in a glass case. (Yup.) One pair of the four that were made for Judy in the 'Wizard of Oz.' He had that one pair. He then showed me an old script for a film with an inscription.

“To Sidney, all my best, Irving Berlin.”

It was a script that Sidney had written, for a movie with songs by Irving Berlin. The movie was Easter Parade - with Fred Astaire and Judy Garland. Then he showed me the script for another film that he worked on… “Annie Get Your Gun.” I couldn’t help but wonder. "How on earth did I get here?” Then Sidney looked me squarely in the eye from his high perch above topped by a shock of white hair - (he was quite tall) -

“You need to play the character of Irving Berlin. I knew him very well. You need to play him.” I already had my sights set on Fryderyk Chopin for the next project.

“Ok Sid, I’ll think about it.”

“Don’t think too much,” he said. “Just think a little, then do.” Wiser words, were not often said. Sidney brought up my playing the role and music of Irving Berlin a great many times over the next few years, and I always put it off. I got busy playing Gershwin around the country, while working on Chopin, and Sidney Sheldon, author of all those great romance thrillers, writer and creator of “I Dream Of Jeannie,” television writer, screen writer, Hollywood and international icon… Sidney who had befriended me because he said I reminded him “of the way it used to be…” died. I didn’t get to say goodbye. The last time I saw him was on September 11th, 2001 – 9/11. I had been invited to stay over for a few days in his guest house, and work at the piano before heading back east to perform. When I came into the breakfast room to join him for our regular breakfast together, he had the TV on.

“Such a terrible thing, in New York. Have you seen?”

And together we watched the tragedy, the second tower falling, the devastation, the disbelief. “The world won’t be the same after this.” He was right. For a time, the world seemed to have gotten more generous. Sidney lived for six more years, he was 90 when he died. We stayed in touch for the first years after the tragedy, but then he became very ill of health and he stopped communicating and seeing people. When I drive past the gate on Sunset when I’m in LA, I still look up and nod, to that wonderful man who first told me that I needed to play the character of Irving Berlin.

The year Sydney died, 2007, I made my first appearance at the Geffen Playhouse playing the role of George Gershwin, for the second time in Los Angeles. There would be several more runs over the years, but this one was sure to get attention. It was the Geffen Theatre after all - theatre to the “stars.” (How I landed up there is another story, for another time, but it ended up being 8 seasons of plays, sometimes two a season, a long time “home" in LA.) Well, the moment I walked through that door, the Artistic Director of the theatre at the time greeted me. His name was Gil Cates, and everyone in Hollywood knew Gil Cates. He was a real Hollywood character in the best sense of the word, and he loved his theatre which he spearheaded and managed to get funding for year after year, while producing the Oscars Broadcast for Global consumption. After a few moments in his presence Gil said to me:

“I’m sure this Gershwin show is just fine. But you need to play the role of Irving Berlin.” Gil apparently seemed to take over where Sidney left off. And so it was, every time I saw Gil, every time I arrived at the theatre with a new character, first with Gershwin, then Chopin, then Beethoven, then Bernstein, and then multiple other plays. There was Gil.

“You need to play Berlin.”

Finally, after almost five years of this going on, I finally asked him - “Ok. I get that you want me to play Berlin. Well, did you ever work with him?”

“Once,” he said. “Almost.”

“Almost?” I said. “Yes,” he said. “Almost.” Ok then, this I needed to hear.

“Well," Gil said. One year, I think Berlin was a hundred years old by this point, and we wanted to start the Oscars off with a big splashy musical number, full of stars. My favorite song has always been ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business' ever since I first saw 'Annie Get Your Gun.' That song explained my life and how I felt about living, and that’s the song I wanted to open the Oscars with. It was known, that even though Berlin was extremely old, he still liked to have a sense of the business and if you wanted to use his music and lyrics for something, especially something like the Oscars, you had to call him.”

“So what did you do?” I asked.

“I got his number from my agent at CAA,” Gil said. “And I called him.” Silence.

“Well what happened?” I asked.

“He picked up the phone, with a raspy crotchety New Yawk accented ‘Hello.’ I told him who I was, that I was producing the Oscars, that we wanted to do a big musical number, and that I would like to use ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business.’

“'You would, now wouldn’t you?' Came the crotchety Berlin reply. 'Good. Go Fuck Yourself.' And he hung up the phone.”

And I thought: what story am I going to tell? “Gil, what?”

And without missing a beat, Gil responded: “Go find out why he was so unhappy in his old age, and you will have a great American story to tell.” I had no idea what Gil was talking about, but after pestering me so much, I finally said to him - “Ok Gil, Ok, I’ll look into it.”

That was last thing I said to Gil Cates in early October of 2011. Three weeks later, he left the theatre in fine form, went to his car in the parking lot across the street, turned the key, suffered a heart attack, and died. He lived until the last moment, and until the last moment he lived doing what he loved. I still miss him, he was a tough guy, as I said, a character, he used to call me ‘one of his goom-bahs’ (I ‘think' it was a term of endearment, one of his ‘gang’) but if he loved you, he would go to the end of the world for you. I ended up giving the premiere of “Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin” at the Geffen Playhouse, exactly three years later in 2014 on the anniversary of Gil’s passing. It is my understanding that it still holds the record for the highest grossing theatre piece in the history of the Geffen Playhouse, but that wasn’t because of me. It was because of Irving Berlin, and Gil had known that that would be the case.

It was only years later, after telling that story about Gil's telephone call to Berlin from the stage dozens of times for audiences who wanted to know all the parts of how the show came into being, that I made an unusual discovery. That discovery was that in May of 1988, Irving Berlin turned 100 years old. A year and a half later, in September of 1989, at the age of 101, he died. What I discovered was that Gil Cates only began producing the Oscars in 1990. Had he called Berlin in those last months of Berlin's life, when according to Berlin’s family members who I later got to know quite well, he was not particularly alert? Or was the story one that Gil imagined in order to get me to pay attention. Whatever the case, it worked, but not without the help of a few more people.

For the next two years after I made that promise to Gil just before he died, performances of the other plays went on, and a play about Franz Liszt was given its premiere. I hadn’t thought about Berlin, or the promise that I made to Gil, that I “would look into it.” Then one day during a discussion with a close buddy, Eva Price, a wonderful producer from New York, about plays that I could do that might be interesting to New Yorkers, she said: “Why not Irving Berlin?” (Here we go again.) I remember making all kinds of excuses, that he really wasn’t a classical guy, that I didn’t know what story I would tell, that I didn’t know what I could do with it, every excuse in the book. Still Eva said: 'well, let’s just meet Ted Chapin anyway who runs the music estate for the Berlins and go from there." Ted is a musical theatre icon, whose parents I knew of because they were icons in the classical music world, his father having produced some of the greatest musicians on record, his mother an actual Steinway of the Steinway family. Sure, I’d meet Ted any day!

Eva and I went up to Ted's offices on a chilly winter afternoon. He gave me a tour and showed me some Berlin memorabilia. We sat in the conference room and talked about Irving Berlin. He knew the daughters and entire family, as they worked together regularly. He asked me if I’d like to meet them. Well, of course I would. I was still not convinced that I could do anything of the sort with the character and material. Ted offered for me to attend the “family meeting” which I suppose took place once every quarter to review estate business and so on. I said I would be there.

The next month Eva and I returned to the offices, and there, behind the conference table were three quite stoic ladies, all naturally grey, but Linda, the middle daughter being the least grey among them. Mary Ellin the eldest, and Linda, the middle daughter were quite petite. Elizabeth, the youngest of the three, was the towering one. It was obvious that each of them saw and processed everything that went on around them, but each in their own way, and each with very clear judgment. Their clothing was not colorful, in shades of grey, blacks and whites, but always comfortably and elegantly put together. They sat on one side of the conference table, observant, somewhat stoic, but never arrogant or unkind. As Ted described them to me “they are extremely well mannered ladies.” And that’s exactly what I was seeing.

By that point I had done some serious reading, not wanting to be flip about anything in their father’s life. And as I sat down, it hit me quite powerfully. Mary Ellin, sitting opposite me to my right, was born in 1927. Her father wrote the song “Blue Skies” for her upon her birth. Because of my studies on George Gershwin, I knew well the life of Al Jolson who premiered Gershwin’s “Swanee.” In studying Jolson, I had studied the first ‘talkie” “The Jazz Singer” - the story of a cantor’s son from Russia who becomes a jazz singing sensation in America to the disappointment of his Old World Cantor father. Jolson sang “Blue Skies” in the picture. The lady I was sitting in front of was for whom the song was written, and the sound film industry as we have come to know it, began with that song. While having read Berlin’s story I certainly appreciated his unsurpassed accomplishments, there was something about this encounter that hit home very deeply. And then the strangest thing - instead of my being there to be “auditioned” by these family members, it became an afternoon of these daughters, auditioning their father’s story for me. The most fun, was hearing one make a statement about their father. A moment of silence and maybe a little tension and then quietly from another...

“That’s not the way it happened.”

And then for the next forty-five minutes, I became the audience for the very familial, amusing, wildly entertaining family dynamic exchange about the merits of facts and what exactly happened. But in the end, there was one thing that they all agreed on that touched me a great deal…

“For years people were critical of our father’s music and his style, they called it corny. But we need to tell you. Our father’s patriotism wasn’t made up, or an act. He really did love this country as much as his songs said he did.”

After that, I decided that I had to do something. At least I would try. That kind of character, that’s my kind of guy.

I gave a call to the guys running the Geffen at the time. The show was booked, the studies began, selection of music made, above all it was clear, simply tell the story of his life. One of the things that the daughters told me that I found very interesting was that other than one or two songs that their father admitted were directly affected by his life, he always made the argument that the songs were about regular people and for regular people - the people who built America. However, it was clear that the songs were indeed based on his own direct experiences, and that is what I decided the show had to be about. Some people are looking for expose´ of dirty little secrets in these kinds of storytelling events. But my own experience is that I have never met a composer, a writer or artist who likes something more than “talking shop,” whether it be the inspiration for an artist’s work, the artistic process, the performance, the audience reception and so on. And so I decided, that that would be true to Irving Berlin and it was certainly true of everything I had ever read about him, and everything those who knew him personally told me about him.

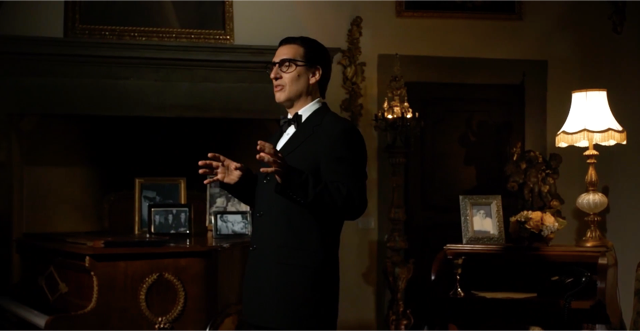

The play opened in Los Angeles at the Geffen Theatre on November 11th, 2014 and has since played some 24 productions in America and the UK, and it holds the box office record in almost all the theatres it has played throughout the United States, but I’m only the messenger. The love for this piece has everything to do with the music, lyrics and character of Irving Berlin.

Over the years a few special things have happened. There was the family gathering at 17 Beekman place, Irving Berlin’s home in Manhattan for the better part of his life, where I performed many selections from the play. There have been the many extended visits with family members, daughters and grandchildren and even great-grandchildren, the gifts of Irving Berlin’s own original paintings, one, a self-portrait, the other an image of a woman in a shawl, one from daughter Linda and the other from daughter Elizabeth, the visit to Linda’s powder room in Paris, where (of all places) family photos that have never been seen by the curious public are stored in stacks that I was able to see. The huge gathering of Berlin family members at New York’s Town Hall for a performance of the piece, followed by a reception at New York’s famed Sardi’s, perhaps the largest gathering of Berlins in many decades I was told; the visit with Berlin relatives all throughout the world who found me at various theatres, that wonderful dinner in 2016 with Elizabeth, Berlin’s youngest, along with Ted Chapin after seeing me on stage as Leonard Bernstein only a few months before she suddenly passed away…the hundreds of thousands of people throughout the world who have been touched by Irving Berlin’s music, and sing along in the theatre, the many rather amazing people I have met because of their love of Irving Berlin, but above all, the sheer admiration I have for Berlin, his art, his family and all the people who love him dearly, and recognize that he may have been an immigrant boy to America, but he understood its people and gave them a voice. I am damn lucky, that I, even for a brief moment, have been able to bask in his eternal light.

Here is a little bit of memorabilia from over the years since this particular journey began…

THE VERY FIRST READING OF HERSHEY FELDER AS IRVING BERLIN FOR BERLIN DAUGHTERS ELIZABETH, LINDA, AND MARY ELLIN

AT STEINWAY HALL NEW YORK.

SUMMER 2014

AT 17 BEEKMAN PLACE, MANHATTAN

SPECIAL PERFORMANCE IN IRVING BERLIN’S ACTUAL LIVING ROOM, NOW THE LUXEMBOURG MISSION TO THE U.N.

APRIL 2016

WITH MEMBERS OF THE BERLIN FAMILY, AT 17 BEEKMAN PLACE,

IRVING BERLIN’S HOME IN NY - INCLUDING DAUGHTER ELIZABETH, GRANDDAUGHTER KATHERINE AND HUSBAND BENJIE AND GREAT-GRANDSON WILLIE,

AND GRANDSON EDWARD EMMET AND WIFE.

APRIL 2016

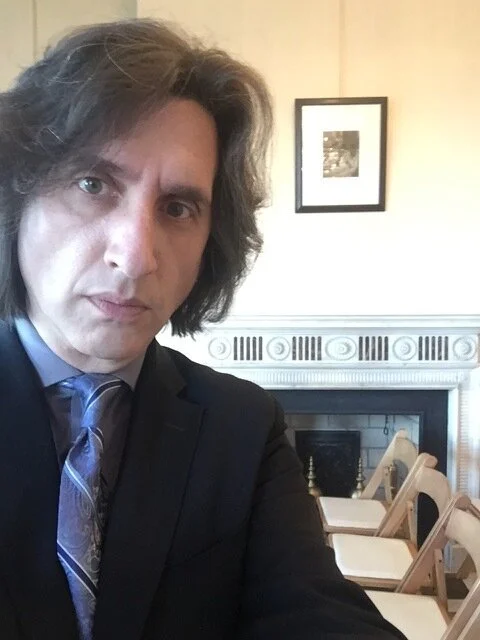

JUST BEFORE THE PERFORMANCE IN IRVING BERLIN’S LIVING ROOM, 17 BEEKMAN PLACE.

APRIL 2016

BOSTON MAJESTIC THEATRE WITH ELDEST DAUGHTER MARY-ELLIN BERLIN, BERLIN GRANDCHILDREN, AND GREAT GRANDCHILDREN.

SUMMER 2015

THE STAGE OF THE MAJESTIC THEATRE IN BOSTON READY FOR A SHOW.

2015

FROM THE STAGE OF THE MAJESTIC THEATRE IN BOSTON FOLLOWING A PERFORMANCE WITH MARY ELLIN

SURROUNDED BY FAMILY SPEAKING TO THE CROWD.

WITH LINDA BERLIN AT HER PARIS HOME LOOKING THROUGH FAMILY PHOTOS, WITH HFP MEMBERS.

FALL 2014

DINNER IN PARIS WITH LINDA BERLIN EMMET, HUSBAND EDOUARD, BERLIN GRANDDAUGHTER CAROLINE, GREAT GRANDSON SAMUEL ,

AND GUESTS.

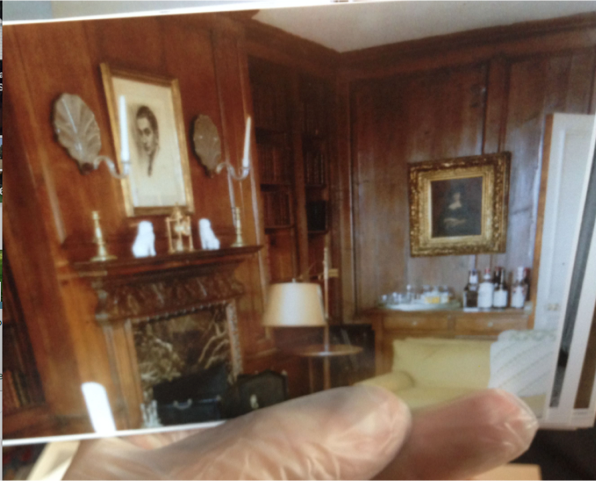

LINDA SHOWING A PERIOD PHOTO OF IRVING’S OFFICE AT 17 BEEKMAN PLACE, THE LIBRARY STILL EXISTS AS IS.

ON THE TERRACE OF 17 BEEKMAN PLACE OVERLOOKING THE HUDSON, WITH MY WIFE, KIM CAMPBELL.

WITH PRODUCER EVA PRICE AT 17 BEEKMAN PLACE, IRVING BERLIN’S HOME.

APRIL 2016

THE FIRST DRAFT OF THE SCENIC DESIGN MODEL FOR THE PRODUCTION.

SUMMER 2014

ELEMENTS OF THE FIRST PRODUCTION INCLUDING THE ORIGINAL PHOTO OF IRVING’S MOTHER, GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE LOS ANGELES.

2014

BERLIN GRANDDAUGHTER, ELIZABETH MATSON, AT THE FIRST PRODUCTION, THE GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE.

NOVEMBER 2014

FIRST BERLIN EYE-BROW EXPERIMENT, GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE DRESSING ROOM.

NOVEMBER 2014

WITH BERLIN DAUGHTERS ELIZABETH AND LINDA, AND HELEN MIRREN AND DIRECTOR TREVOR HAY

AT SARDI’S IN NY AT POST PERFORMANCE RECEPTION.

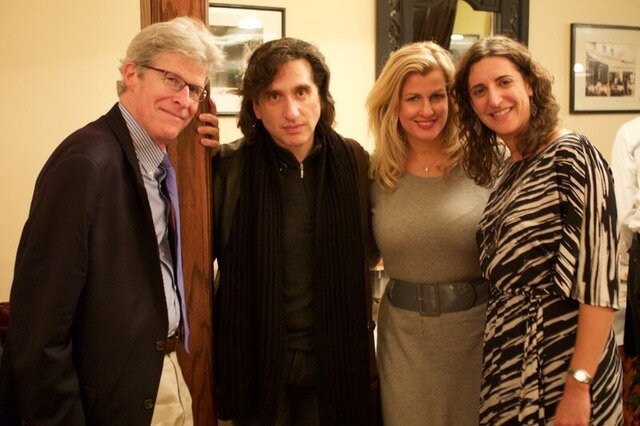

WITH TED CHAPIN, EVA PRICE, AND PR DOYENNE NOREEN HERON AT CHICAGO OPENING, ROYAL GEORGE THEATRE.

2015

WITH BERLIN DAUGHTER, MARY ELLIN, AND GRANDDAUGHTER ELIZABETH AT 59E59 THEATRES, NEW YORK, POST PERFORMANCE.

SEPTEMBER 2018

ELIZABETH, LINDA, AND MARY ELLIN BERLIN AT NEW YORK’S TOWN HALL

HOLDING THE PROGRAM FOR THE SHOW.

JUNE 2016

APRIL 2020 WORLDWIDE PANDEMIC LOCKDOWN, IN MY WRITING GARRET IN FLORENCE ITALY, WITH THE GIFT RECEIVED

FROM ELIZABETH BERLIN JUST A FEW MONTHS BEFORE SHE PASSED.

ABOVE MY SHOULDER - A PAINTING OF A WOMAN WRAPPED IN A SHAWL

PAINTED BY IRVING BERLIN, 1972.

PRESS ARTICLES

AMERICAN THEATRE

‘Hershey Felder as Irving Berlin’ to Stream Live as Benefit for U.S. Arts Orgs

THE SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE

Live from Italy: a Mother’s Day fundraiser for San Diego Rep and other U.S. theaters

THEATERMANIA

Hershey Felder to Present Irving Berlin Benefit for 13 Theaters Across United States